German elections: implications for European security and defence

24 February 2025

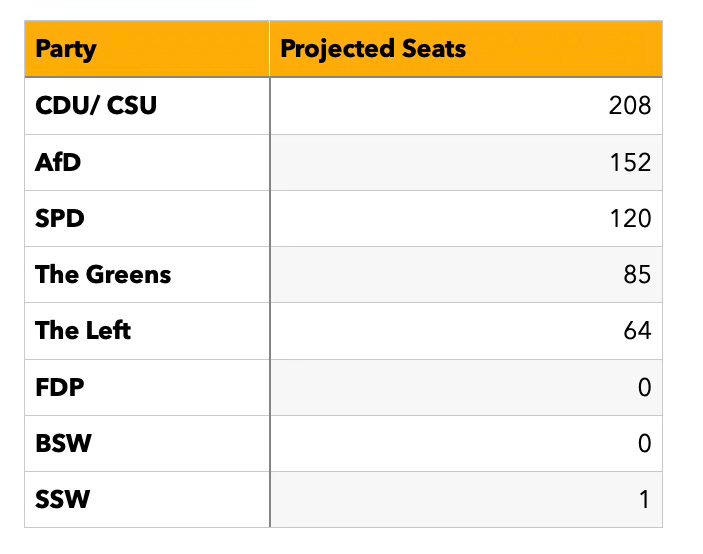

Germany has voted — and the election night kept observers awake and glued to screens until late as the final composition of the Bundestag (federal parliament). Especially the numbers of parties represented and hence the options for coalitions was still up in the air. At 6:00 CET, 24 February 2025, the preliminary result looks as follows:

Preliminary results: second vote percentage and seat distribution

Source: own creation, based on Federal Returning Officer of Germany

Based on this calculation, a coalition composed of CDU/CSU and the SPD (centre-left, Social Democrats) seems possible, as this combination would hold 328 of the necessary 308 seats in parliament; politically, it is also the more likely scenario than a coalition of three parties, which could include the Greens. CDU’s lead candidate and likely next Chancellor Merz has excluded any form of cooperation with the AfD (far-right), and the CDU’s party line generally rules out cooperation with the Left Party.

The result of the elections will have a significant impact on the country’s approach to European security and defence, as well as Germany’s foreign policy more generally. Here’s what to expect — and what not to expect.

(1) Do not expect changes from day one

The most important implication of the elections, especially for Germany’s European and international partners thinking about potential shifts in German foreign and security policy, is that change is not immediate.

The CDU will need at least one coalition partner, and forming a coalition can be expected to take at least until April. Once a coalition agreement is signed, the Chancellor will be elected in the Bundestag (parliament). Until then, the current government will remain in office and lead the country as a caretaker government. During the TV debate among all lead candidates on Friday evening, Merz set out the ambition to finish the negotiations by Easter (20 April).

The newly elected parliament must convene for its constitutive meeting no later than 25 March, but this can happen earlier, which would also allow voting legislative proposals related to foreign policy. However, any important vote is unlikely as the legislative process usually involves work in the committees, which will not start before the constitutive meeting, and neither the parliamentary groups nor the government would initiative new legislative proposals, unless the caretaker government decides to do so.

(2) A united front on Ukraine (at least publicly) — and no discussions on “boots on the ground” in Ukraine

The elections will not significantly revisit Germany’s position on Ukraine: there is overall broad consensus among CDU/CSU, SPD, and the Greens that German support to Ukraine has to continue. Even when the coalition agreement is still being negotiated, one can expect Germany to pursue its current approach and also push for more EU support.

However, the key questions are “how much” — in terms of the support Germany provides to Ukraine (buzzword: Taurus delivery or no Taurus delivery?), the exact financial contribution, and how all this can be included in a German budget. The delivery of Taurus missiles is requested by the CDU/CSU and the Greens, but still-Chancellor Scholz and parts of his party are strongly opposed to this idea. Significantly stepping up support for Ukraine will also require Germany to revisit its budget and most likely the so-called “debt break”, but after the CDU has blocked the reform of this instrument before the elections, it will be increasingly complicated to find the majority for this endeavour, which requires a change of constitution, in the new parliament.

Another key question regarding Ukraine will be the importance of following the US line. Following his visit in Paris for the European emergency summit in mid-February, Chancellor Scholz underlined the importance of cohesion of transatlantic partners and avoiding fragmentation between Europe and the United States; in contrast, Merz has more openly criticised President Trump’s approach to Ukraine, although it remains to be seen to what extent he would be willing (and able) to oppose a US position if it contradicted European interests.

While discussions on peacekeeping troops or a European “reassurance force” are taking shape in France and the UK, one cannot expect any strong statements on this question from any party leader in Germany. When the topic arose in the TV debate on election night, both Merz and Scholz categorically excluded to even discuss this topic, arguing it was not the salient debate to be held at the moment. European partners eager to advance this proposal will have a hard time finding a willing interlocutor in Berlin.

(3) Between atlanticist tradition and risk of transatlantic abandonment: calls for a European strategic autonomy from Germany?

In light of the recent announcements of the United States regarding European security and the start of meetings with a Russia on Ukraine, German foreign policy might see an unexpected shift away from especially the CDU’s diehard-atlanticist approach.

During the TV debate on election night, Merz found (astonishingly) clear words on the United States. After stating that the US administration was “largely indifferent regarding the fate of Europe”, he outlined that Europeans would have to do much more for their own defence. Talking about the NATO summit in The Hague, he emphasised the need for a stronger European defence and the risk of abandonment by the United States. Although emphasising the need to “keep the Americans on board”, the debate demonstrated that Merz’ approach to European security might come closer to proposals from France and the European Commission than one could originally expect. The CDU’s election programme still reads partly like a transatlantic manifesto with a clear focus on the transatlantic alliance and the idea that the United States will remain a reliable partner for Germany in the future; and albeit a francophile, a “transatlantic reflex” seemed to be in Merz’ foreign policy DNA. Yet, the events in the last weeks seem to have profoundly shaken these beliefs, and Merz now appears clear-eyed about potential risks from Washington: in the TV debate on Sunday night, he outlined that “interventions [in the German electoral campaign] from Washington were not less significant than the interventions from Moscow”, just after remarks earlier last week that Germany should potentially discuss nuclear protection with France and the United Kingdom.

This turn away from the CDU’s originally very NATO-focused position and a clear commitment to European defence, if necessary without the US, could also morph into calls that strongly align with the agenda of French President Macron and the European Commission — namely European strategic autonomy and much more ambition for European security and defence. Especially as a long-standing ambition of the CDU is centralising more competence for European affairs and for security policy, in form of a national security council, in the Chancellery, one could expect Merz to quickly seek synergies on this topic with key European partners.

(4) An opportunity for reviving the Franco-German relationship for new ambition for and co-leadership in Europe

The hopes for more fruitful cooperation with Germany on the highest political level are particularly high in Paris. While cooperation on the working level, as well as among ministers (think of cooperation formats of the foreign ministers, like to co-organised humanitarian conference on Sudan, or stronger ties in defence policy like the Main Ground Combat System), the relationship between French President Macron and Chancellor Scholz never morphed into an ambitious Franco-German engine for Europe.

Merz might, indeed, easily find synergies with French President Macron on key questions. When the two men met already back in 2023 — it was a relatively uncommon gesture by a French President to meet Germany’s opposition leader —, the mood was generally described as good. Merz, politically rooted in Western Germany, is said to be francophile, and might indeed align with Macron on questions like trade, tech, or, most recently on the background of the Trump administration’s approach to Ukraine, European defence. However, disagreements on key questions will remain, and especially diverging positions on common debt, for example for financing European defence through “Eurobonds defence”, could create tensions. Furthermore, it is also important to underline that many frustrations of European partners with Germany’s Europe policy in the last years, such as divergent positions of different ministries in votes in Brussels or lengthly decision-making processes in Berlin, are the result of a coalition government; even if Merz, as announced, managed to better align ministers, Berlin would still need to strike compromise at home before advancing a position on the European level.

When asked about his first foreign trip as a Chancellor, Merz indicated he wanted to visit Warsaw first, followed by Paris — which would also be an opportunity to revive the Weimar triangle. In recent months, the E5 format, bringing together France, Germany, the UK, Poland, and Italy, has additionally gained traction, and it is likely for Germany to pursue this path.

A key opportunity for the Franco-German relations consists in aligning their views on the transatlantic relationship. The relationship between Paris and Berlin has significantly suffered from the almost diametrically opposed conclusions drawn from Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, with an “all in for European sovereignty” in Paris and “all in for transatlantic cooperation” in Berlin. As both are now forced to adapt their views to the new administration, newly emerging synergies could benefit both a Franco-German and a broader joint European approach in terms of security and defence.

(5) Germany’s policy towards China: the balancing act continues

A new government will also have to focus Germany’s approach to Beijing — either through implementing or amending the German China strategy published in 2023. Especially at a time where ties with the United States are challenging, to say the least, new dynamics in the German-Chinese and EU-Chinese relationship might render this approach more complicated.

A significant shift in Germany’s approach to China seems, however, relatively unlikely. Even within the parties that might join the governing coalition, especially the CDU/ CSU and the SPD, the desirable approach towards Beijing is contested: while some emphasise the importance of economic ties with China, notably at a time of a looming trade war with the United States, others call for a much tougher approach towards Beijing. If they join a governing coalition, the Greens will certainly push for a more confrontative approach with Beijing, emphasising the increasing element of rivalry in the EU’s triple approach to China as a partner, competitor, and rival.

While China will be undoubtedly be on the foreign policy agenda of the new government — not at least because the approach towards Beijing directly impacts Germany’s position on key questions of EU policy, such as trade or technology —, one should manage expectations in this regard. The key foreign policy priority of the new Chancellor and the government will most likely be the response to Russia’s war against Ukraine and strengthening European defence, and there will be limited bandwidth on the highest political level to prioritise relations with Beijing on the short-term.